|

| back |

More Learnng Center articles >>

JUNE 13, 2000

|

In politics as in affairs of the heart, building trust remains that most elusive ideal. But creating it in your workplace could be your greatest competitive advantage.

Trust Fund

By Arky Ciancutti, M.D. and Thomas L. Steding, Ph.D.

We are a society in search of trust. The less we find it—in government, in business, in personal interactions—the more precious it becomes. An organization in which people earn one another's trust, and which commands trust from the public, has a powerful competitive advantage. It can retain the best people, inspire customer loyalty, reach out successfully to new markets, and provide more innovative products and services.

What many people don't realize is that you can intentionally create trust in your organization. You can drive a culture of earned trust that includes everyone in the company and harvests, at virtually no additional cost, opportunities to increase growth, profit, productivity, and job satisfaction.

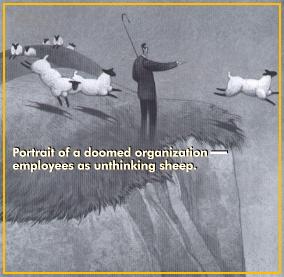

We use the term Leadership Organization to mean one in which leadership consciously and intentionally creates a culture of earned trust. The alternative is a Random Organization, one that relies on arbitrary and accidental habits of interaction within its work force. Random Organizations are almost always fear-based, reactive, obstacle-oriented, and influenced by a "Them vs. Us" mind-set with all its negative financial, personal, and productivity consequences. With Internet hyperdrive in full gear, today's fast-paced business environment demands a new approach to leadership that avoids these common pitfalls of negative culture.

IBM was one of the first major corporations to learn the value of earned trust. Over the years of its market dominance, it inadvertently developed a culture that punished sound risk that failed. People became very careful—more careful than they were creative. Some played defense and watched their backs. A bureaucracy grew up, partly based on a sense of entitlement. Innovation and mutual trust suffered. By the late 1980s, some people were as concerned with looking good to top management as they were with market performance. The result: IBM nearly failed. When it examined its culture, IBM discovered how much damage risk aversion had caused. Beginning in 1991, IBM developed risk guidelines that enhanced trust, and executed one of the most dramatic turnarounds in business history.

The new competitive edge

Free markets demand that we keep our competitive edge. But to the business manager scrambling to keep up, Adam Smith's "invisible hand" often feels more like a clenched fist jammed into the small of the back. One after another, management theories emerge and capture the collective imagination of the market, only to fade from sight, and our business bookcases read like a fashion parade passing in review.

Perhaps we are stuck. We have been preoccupied for almost a century with the notion of organization as machine. This model deals with what can be observed, measured, manipulated, structured, and modified. Early fascination with time studies—organizations as clocks and people as cogs—gave way to business process re-engineering and time-based competition, both essentially mechanistic perspectives on competitive advantage. While each new trend provides some measure of temporary advantage, its incremental return from additional investment eventually vanishes as it becomes established best practice. Further, and most important, these methodologies can be copied easily, and therefore cannot represent a sustaining competitive advantage.

Even our language reflects the idea of organization-as-machine. We speak of systems, hierarchies, structures, processes, interfaces, and cycles. We step on the gas, take off like a rocket, smash one out of the park, turn up the heat, restart the program, hit the wall. We seem trapped in a mind-set of externals, pursuing the management program du jour to try to squeeze a little more blood out of something that looks increasingly like a turnip.

| "New business thinking looks for competitive advantage in the realm of the human spirit." | |

New business thinking looks for competitive advantage in the realm of the human spirit. As we step into this territory, we begin to deal in meaning, trust, inspiration, depth, paradox, transcendence, and connection—as well as with their dark-side counterparts: doubt, fear, conflict, isolation, and just plain feeling stuck. The search for competitive advantage is shifting from the exterior to the interior, and departing radically from the metaphor of organization-as-machine. It is looking into the far more spacious realm of the collective team mind for a new kind of resource.

Another concept under discussion is social capital, the emotional or psychological equivalent of financial capital. Social capital can take the form of trust, acknowledgement, appreciation, or the knowledge that in supporting you, colleagues are doing something that is consistent with their personal values.

Francis Fukuyama, in his Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (Free Press), examined the differences in economic prosperity among different cultures and concluded: "A nation's well-being, as well as its ability to compete, is conditioned by a single, pervasive cultural characteristic: the level of trust inherent in the society." In our current global struggle for economic predominance, he believes that "social capital represented by trust will be as important as physical capital."

Robert Putnam, author of The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life, builds on the notion of social capital as "features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit." He traces success to an abundance or lack of social capital.

The same principles apply in individual businesses. Trust represents enormous social capital with customers. Further, we know that the social capital of trust works within organizations to create connections and cohesion among team members, which leads to greater productivity.

Why trust works

The principle behind the Leadership Organization is that people have an innate, passionate desire to contribute. Opposing this urge to contribute is fear—fear of rejection, failure, loss, retribution, or embarrassment. Sometimes we hang in the balance, afraid to go this way or that, standing at the end of a diving board, not wanting to jump and not wanting to climb back down. While people's passion to contribute may not be obvious at first glance, below the surface almost everyone wants to be productive, to know that their organization is a better place because of what they do each day. Fundamentally, motivation is almost never the problem.

The problem arises when people think that their opportunity to contribute has been thwarted. What they want most is no longer available to them, or so they think, and they withdraw, become defensive, gossip, cause trouble, or start just going through the motions at work.

Suppose you have a great idea for a product and want to take it to the board, but you are afraid some board members might object to it. You deliberate about when, where, or even if you should bring it up. Eventually, you go ahead with the presentation. They don't seem very interested. They interrupt your presentation, and you can tell by their questions that they're not really listening. It's not even that they disagree with you; they just don't seem to be engaged. How would you react? Or suppose you present your idea to the board, and they are completely opposed to it. How would you react then? Or suppose they love the idea! You are now the organization's new genius, the rising star who can do no wrong.

Your responses to these different outcomes may range from frustration to elation, but your reaction will always be emotional—and it will be based on how well your desire to contribute, and the risk you took to make that contribution, seemed to be received. Our passion to contribute is always delicately balanced against our instinct to protect ourselves—and there is an important emotional consequence, positive or negative, each time we take the risk to contribute and be productive.

Feeding the passion to contribute

Earned trust tips the balance between the urge to contribute and fear. When we work in an environment of trust, and one in which leadership models trust, we feel reinforced, validated, and supported, even when our ideas are not accepted. We are far more likely to plunge in, to be creative and generous with our talents. An organizational culture of trust makes us want to support and contribute to the company.

In a Random Organization, on the other hand, the ability to contribute is hit-or-miss. Sometimes people can contribute and feel great. Other times, they wish they'd never opened their mouths. Nobody really knows how it will turn out, because nobody is in charge of setting an emotional direction for the organization. There is no one to tip the balance in favor of contribution by consciously creating an environment of trust and respect.

Carmen was recruited from her position as senior vice president of sales for a cable TV station, where she was a seasoned and celebrated success, to a similar position in an emerging Internet company. Everyone assumed she knew exactly how to build a sales force in this new medium, but she did not. In those days, everyone in Internet sales was a pioneer. This was Carmen's dilemma: Should she admit she didn't know what to do and ask for brainstorming help from her fellow executives, or should she continue to bluff and tough it out?

The rational answer is obvious, but the emotional environment could make it difficult for her to execute. If she could ask for help without fear of people judging or denigrating her, Carmen could access the combined experience and intelligence of the connected team, use them to network into other sources of information, and certainly do a better job of building and directing her sales force.

The connected team

The connected team combines not only the intellectual assets of the individual participants, but also their instincts, hunches, dreams, aspirations, creative imaginings, gut reactions, musings, and moods. When people feel free to contribute all their resources, they create a larger network of intelligence. In a fear-based environment, we only reveal what we feel is safe, which might be only a small part of us, and the leader ends up trying to conduct a symphony with one-string instruments.

The effect of the connected team is to create a new form of superordinate intelligence, where team intelligence grows nearly exponentially with an increasing population. Now, the strong interplay among team members creates an upward spiral of creativity as ideas are exchanged readily and improved continuously.

The connected team is not just another management fad providing a temporary form of competitive advantage; it is the creation of the underlying capacity of the organization to create limitless forms of competitive advantage. It is the generator of technique, not technique itself.

| "In a fear-based environment, we only reveal what is safe, which is only a small part of us." | |

The business case for trust

Some of the specific business advantages arising from the connected team are:

Sustainable competitive advantage. An environment rich in trust creates an engine for innovation. There is no upper limit to the combined intelligence and creativity of the team - and no team is just like any other, because each team's true identity emerges in the safe environment of mutual support. These teams can extend trust authentically to the customer, resulting in an extraordinary level of loyalty.

Self-regulation. People at all levels of the organization are inspired to identify and resolve open issues without unnecessary or intrusive supervision by leadership, and to relate with one another in a framework of trust guidelines. People become committed to developing habits of reliability, follow-through, and clear communication.

Efficiency. In a passionate organization that does not consciously build on trust, everyday frustrations result in "Them vs. Us" interactions. The business built on trust principles eliminates this energy lost to suspicion, unresolved issues, forgotten commitments, unclear agreements, missed deadlines, and the associated propensity toward blame, gossip, resentment, and frustration. All of this energy then becomes available for productive use. On the connected team, somebody always knows when a particular issue has not been resolved, so you do not have to wait for the customer or the marketplace to show you that you are off-track.

Inspired performance. The connected team discusses and processes ideas at every stage, so incremental "fixes" and improvements can be made as needed. Ideas pass through many hands and are improved at each turn, so these teams have an unusual ability to create superior products and services.

Capacity for change. Trust-based organizations have a knack for holding opposite conditions and points of view simultaneously. They may, for example, have tightly structured, disciplined development processes, and yet still be able to react quickly to changing market needs or internal situations such as mergers. The connected team is a crucible that can stand the heat and contain its reactions until a new synthesis is reached.

Meaning. Making trust a central principle anchors the organization in a set of values that everyone agrees is attractive and meaningful. People become part of something bigger than themselves—and that results in attracting the best people, and keeping them happy and creative.

Creating trust quickly

Trust is a dual concept. It has both a feeling or emotional component, what Webster's calls "assured anticipation; confident hope," and an intellectual component. This intellectual component is based on a track record of performance that confirms trust, or "assured reliance on another's integrity, veracity, and justice." The active result of trust is confidence in the honesty and reliability of the company's leadership. The passive result is the absence of worry or suspicion.

|

Trust, then, is confidence, the absence of suspicion, confirmed by track record and our ability to self-correct. Building the culture on trust not only covers all these bases—emotional and intellectual, active and passive—but it also works quickly, which is essential for success in the marketplace. We know that it can take up to two years to establish trust between individuals. This is why we reserve our greatest trust for our most established relationships—our family, long-term friends, and social circles. But in business, we are in a hurry. Time is of the essence. Two years includes eight financial quarters, more than enough time to perish in the current economic climate. We need something faster and more efficient. We begin to address the issue of speed by observing a general principle. Folk Theorem I: People are more willing to trust, more quickly, when principles that promote trust have been explicitly and universally adopted. |

|

We are willing to continue that trust for as long as people's behavior, particularly the behavior of key leaders, is consistent with those principles. Provisional trust, confirmed by experience, then deepens into institutional trust.

So rather than waiting two years to establish trust, building earned trust through guidelines and principles facilitates a substantial level of trust in only a few weeks, the time it takes to develop your particular trust principles, and a short period in which people watch others (especially the leaders) demonstrate their adherence to it.

| "The Connected team is a crucible that can stand the heat and contain its reactions until a new synthesis is reached." | |

Built on trust

The tool we offer for creating a culture of earned trust is the Trust Model. The Trust Model is an ongoing process of examining the specific areas in your organization that must be addressed in order to build a culture of trust—these might include growth, profitability, closure, commitment, communication, speedy resolution, respect, and accountability—and within that process, creating and continuously updating your own customized set of Trust Model guidelines.

Your Trust Model guidelines are framed and modeled by leadership as unilateral promises, and then offered to the entire organization in a systematic way for everyone's input and buy-in. People at all levels of the organization participate in developing and shaping them. Building your guidelines requires everybody's involvement, contribution, and creativity—and the process of drafting your guidelines, communicating to the organization about them, earning acceptance for them, and maintaining and evaluating your Trust Model are all part of that trust-building. The Trust Model is truly a continuous process, not a set of rules. The leadership and organization may wish to consider certain principles for inclusion in its own Trust Model. What follows are two key examples.

Is your firm built on closure?

Closure means coming to a specific agreement about what will be done, by whom, with a specific date for completion. You don't leave anything dangling. "I'll get you the report" isn't closure because there is no time by which it will arrive. "I'll do what I can" isn't closure because there is no specific agreement for what will be done. It's easy to see how lack of closure breeds uncertainty, hesitation, doubt, wasted time and energy, resentment, and lack of trust.

Here's how it works. You are sitting in your office and Henry sticks his head in the door. Seizing the moment, you ask, "Henry, would you get me a ham sandwich?" Henry disappears without comment. Now it begins. You start wondering: Did Henry hear me? Is he going to get me the sandwich? When? Who will pay for it? Does he have the money? Or is he upset that I asked him in the first place? Does he remember that I got him a sandwich last week, or did he forget (which would be just like him)? Did Henry's mother teach him any manners? And what about the mustard?!

Lack of closure always leads to wondering, which takes time and energy away from other tasks. Wondering is gyroscopic; we sit and spin in place, consuming momentum, going nowhere. Even if we try to shove the concern from our minds, it simply resurfaces later, perhaps in the middle of the night. ("What did happen with that sandwich?") And the greater our passion for success, contribution, and satisfying the customer, the more consuming the worry.

In a culture of closure, you can simply ask for a date for an action. Then you can spend the time between now and that time doing other things—not wondering and worrying about whether or not you should call, whether or not anything is being done, or when it might get done if it hasn't been important enough to do up to now.

Wondering breeds suspicion, and suspicion is antithetical to trust. Therefore, closure is critical to trust. The goal of a Leadership Organization is to have 100 percent closure on all communications, big and small.

| "Lack of closure always leads to wondering, which takes time and energy away from other tasks." | |

False commitments

Commitment is an "intention of no conditions." This means that there are no hidden "ifs," "ands," or "buts." It doesn't mean that you absolutely guarantee the result that you promise, but it does mean that you enter into the commitment with every intention of fulfilling it. And if you discover that you can't keep the commitment for any reason, you speak up immediately.

A false, half-hearted, or pretended commitment is saying "yes" without the pure intention to produce the final outcome on time. When we go into an organization, one of the first questions we ask is, "How much of the time do you think people really mean what they say?" The answer is usually 20 to 60 percent.

False commitments can be made consciously or unconsciously, with or without malice aforethought. In most cases, nobody means to make false commitments; they are just one of our workplace habits. They are sometimes called "nodding commitments" or "hallway salutes." In the mind of the person making the commitment and not following through, the false commitment may seem like no big deal. It was a lapse in memory, an excusable detour, an avoidance of the inconvenience of following through, or a change of heart—things everybody does, for heaven's sake! The person to whom the false commitment was made, and who is still relying on it, is still heading for a destination that will not be there when he arrives. His reaction may range from irritation at the minor inconvenience of having to revisit the issue and establish a new commitment, to there being absolute hell to pay.

You may have experienced pretended or false commitments when people have said to you, "I'll get you the report," "I'll make it up to you later," "The check is in the mail," or "I'll get right back to you on that." If you didn't get the desired result, you were probably disappointed, angry, hurt, or simply less likely to trust that person the next time he or she promised something.

In an organization that winks at or even encourages pretended commitments, people stop believing what others tell them. When they can't count on what others tell them, they try to stop caring. The trouble is, they can't stop caring. The passion to be productive and helpful still lives, even if it's below the surface. When we can't contribute, we hurt. We may disguise our hurt in ways that look cavalier, defensive, or even aggressive, but the pain of not contributing eats away at us and saps our energy.

We may even start making promises that we have no intention of keeping. We then start believing that we can't have integrity at work, because we have to say we'll do things we either can't do or aren't willing to do. We begin a cycle of not doing what we said we would do, then finding excuses.

Folk Theorem II: False commitments lead to dramatization in the organization. False commitments bleed the team of energy in many ways. People first have to stop and figure out how to get the work done that was promised but not delivered. Then they have to fix the mess that they are probably in because the work didn't get done with the original commitment. They also have to deal with knowing there is someone in their midst who says one thing and does another. The habit of making pretended commitments creates a downward spiral in organizations. People trust less, and fear more. False commitments may begin with the lead team, but they eventually work their way down through the organization to the customer. A customer who knows you make false commitments isn't likely to be a customer for long. The habit passes as a business practice only because our competition is probably doing it, too! |

|

Folk Theorem III: If you are learning about problems from your customers or the marketplace, it is already too late.

The worst-case scenario with false commitments is that they go undiscovered for a long period of time, say, until the first external measure of progress arrives. That could mean the first quarter sales figures, or the testing of the new software program, or a customer complaint. At this point, the false commitment is much more costly and time-consuming to correct. Not only have time and energy been lost, but it may be difficult to locate the original false commitment.

Folk Theorem IV: At least one person on the team always knows about a problem well in advance of it being revealed by customer complaints.

A networking startup company experienced a predicament that illustrated Folk Theorems II-IV. On August 19, this company shipped a "beta card" to a reselling partner, who happened to be a very large networking company. The "beta card" was a very complicated product, and the customer had an internal delay of at least two months before it could start testing it. When they finally did the tests, the card crashed repeatedly. The customer was upset because the project was already behind schedule, and threatened to cancel the order if the software company didn't make the "beta card" work within 10 days.

The startup took them seriously and had engineers working around the clock to make the deadline—which they ultimately missed. But during the final press to finish, one of the engineers said, "They should be mad at us. That card was a piece of junk."

His comment revealed that as early as August, when the beta card was first shipped (and possibly long before that), somebody on the team already knew that it wasn't going to work, but hadn't told anybody. Somebody always knows, and it's inevitable that the problem will radiate out to the customer. At that point, it's often too late to fix the product, and the result is lost energy, time, reputation, and business. If our startup had been aware that the card was "a piece of junk" back in August, we could have gotten to work fixing it during the two months that it was sitting over at the customer's office, not being tested. The result would have been a good product, less stress and overtime, and far less "Them vs. Us" among individuals and the two companies.

|

Folk Theorem V: You can only honor commitments to customers to the extent that you honor commitments internally. False or pretended commitments are so common that we can sort them into categories. One category is "being late." Late to the meeting, late to the plane, late to work, late to your own funeral. Showing up late means that the person made a false commitment about starting on time. The drama, the wasted energy, the wondering, and the downward cycle begins immediately: "Where is Phil? Is this meeting on his calendar? Maybe we should check with his administrative assistant. He told me yesterday he'd be here. How are we going to restructure the agenda? Why is he always late? Doesn't he know that we're busy, too? Does someone have to be somewhere else after this meeting or can we extend it? Doesn't anybody give a damn around here?!" |

|

Much of the frustration of everyday life can be traced to false commitments. Bounced checks, late deliveries, shoddy work, unreturned emails, laundered shirts with missing buttons, poor work performance, broken partnerships, and so on—under close examination, all of these involve issues with "commitments" that were made but not kept.

An organizational culture in which people consider their commitments carefully, and in which they absolutely intend to do what they say they will do, generates trust. People can relax into their natural enthusiasm, without fear that they'll be let down, and feel part of something bigger. When we encourage people to earn trust, and show them how, everybody's goal becomes the same. That translates into greater commitment, greater creativity, greater satisfaction with work, and better performance.

Many problems with commitment come in the making and not the executing. An effective environment must make adequate accommodation for the serious nature of commitments. We can begin by providing adequate opportunity to weigh commitments in the making, which means honoring doubt in a new way. Doubt is an invitation to examine the proposed commitment. Doubt needs to come out of the closet and into the conference room where it can be visibly present without prejudice. Doubt denied or discouraged will take its revenge later when time, productivity, and trust are lost.

| "Doubt denied or discouraged will take its revenge later when time, productivity, and trust are lost." | |

Folk Theorem VI: Genuine doubt virtually always precedes real commitment.

In addition to examining closure and commitments for improvements, there are other areas that can yield substantial performance improvements. One of them is "Them vs. Us."

Harvesting "Them vs. Us"

|

"Them vs. Us" is the frequent appearance of two or more adversarial elements in the organization. Them vs. Us is so automatic, so fateful, so commonplace, that we are tempted to conclude that it is an inevitable destiny of teams, and we enjoy endless jokes about engineering versus marketing, marketing versus sales, and HR versus just about everybody. We don't think this outcome is inevitable. We think Them vs. Us arises because people care about the outcome of their work, and the outcome is thwarted due to lack of closure between groups. Finding new forms of closure, and collaboration, between heretofore warring elements leads to innovation. When engineering and manufacturing collaborate on designing manufacturable products, we get concurrent engineering. When manufacturing and distribution collaborate on reduced delivery cycles, we have just-in-time manufacturing. When everybody collaborates, we have strong-form cross-functional teams, considered essential for cycle time reduction. These are all specific examples of: The Fundamental Folk Theorem of Competitive Advantage. The greatest prospective opportunities for competitive advantage arise from the most virulent current instances of Them vs. Us in the organization. |

|

There are in fact an infinite number of ways to gain competitive advantage by harvesting the tension in Them vs. Us. Your next great advantage is lying there in the white spaces in your organization chart, awaiting discovery.

An important clue to locating the areas for highest payoff in your organization can be found in your discomfort. We invite you to try the following. In the next 24 hours, think about where you sense lack of resolution or conflict in your team. Then get your leadership team, or your immediate team, together and communicate your discomfort and ask for their input. Don't be surprised if they have been sensing the same issue(s). Ask for their help in identifying precisely the nature of the conflict, and for ideas for win-win closure. Listen carefully. Ask for true commitments, with realistic timelines, and enjoy the process of following progress together with your reconnected team.

ARTHUR CIANCUTTI HAS TAUGHT TEAMWORK AND CHANGE AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY'S GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS. HE IS FOUNDER OF THE LEARNING CENTER. CIANCUTTI IS AUTHOR OF BUILT ON TRUST: GAINING COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN ANY ORGANIZATION.

Try a Free Issue of Business 2.0: Call (800) 317-9704

More Learnng Center articles >>

|

For free consultation on your critical team/leader/performance

issues, or leadership training seminars in California or your own state/country email info@learningcenter.net . |

back